* * *

|

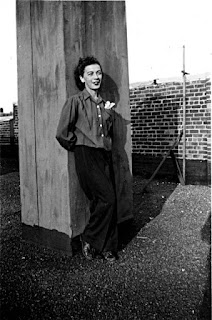

| Anita’s aunt Freda |

Anita S. Pulier

My father’s unmarried older sister Aunt Freda was completely devoted to my parents and us three kids.

I took her for granted. At every holiday and birthday she was there. If any one of us needed something she was ready to help. Of course, she had her odd ways and pronounced idiosyncracies... to me they were endearing.

On her death bed she confessed to me that in all the years I had assumed she was alone she had had a secret lover, the owner of the large meat distributor where she had been the office manager.

He became the butcher in my poem “The Butcher’s Diamond” which is the title of my first full length book that Finishing Line Press is publishing this year.

Gill McEvoy

My outstanding memory of this aunt is this: one day when this aunt was staying with us my mother demanded I take Aunt Vi out walking just so my mother could get on with cooking lunch (Auntie Vi was doing her usual bit of talking away about the insubstantial and my mother was a pragmatic soul who simply wanted to get things done). I took my aunt on my favourite walk, over two Gloucestershire hills and up through a wood to a dry-stone wall, beyond which you would always get the most spectacular view of the Severn Plain, with Wales hazy in the distance. As it was uphill to the wall, the view sprang itself on you with a suddenness that took most people by surprise, and no-one, but no-one, had ever failed to gasp at the sheer magnificence of it. Almost everyone I’d taken there would linger for some time to admire and exclaim. But not Auntie Vi. She didn’t even see it. I was truly taken aback for my aunt, having lectured the whole way, reached the wall, climbed over it without breaking stride, carried on down the far side and was still jabbering on and on when we reached home again. She then talked right through lunch, about how cabbages have souls and we shouldn’t cut them, while all the time cheerfully shovelling rabbit pie and buttered cabbage into her yapping mouth. I never took her on another walk!

|

| Anna’s nephew Isaac |

Anna Woodford

One of the best conversations in my life was with someone who couldn’t speak. It was on a car’s back seat somewhere in 2007 with my new nephew Isaac. Being completely clueless on the baby front at that point, I was trying to get him to say words (unlikely at a couple of months old and, looking back, I was obviously sabotaging his nap time but my brother and sister-in-law who were in the front of the car were either too kind or sleep-deprived to say so).

Isaac’s new word was ‘Ah-ba’. I tried him with ‘Aunty’ and ‘Anna’ (egotiscal, much?!) but he kept smiling delightfully and repeating ‘Ah-ba’. In what Oprah might call an ‘A’ha’ moment, I realised he was actually the one teaching me* – to relax and not to rush on to the next thing and to enjoy the experience of communicating without words. My poem ‘Travelling with Isaac’ came from this experience.

*It was one of many things I learnt from my nephew Isaac – although these days, it’s more likely to be the offside rule.

Charlotte Eichler

The poem ‘Survivors’ is inspired by early memories of visiting my father’s family in Sheffield. My grandfather, Bertold Eichler, came to England from Czechoslovakia in 1939. He was Jewish and had been politically active in smuggling people out of Germany. A local policeman warned Bertold that his name was on a Gestapo list, so he escaped across Poland in an empty petrol tanker. His immediate family died in concentration camps, but one of his close friends, Edith Rosenberg, survived Auschwitz, was reunited with her husband, Otto, and settled in a flat in London.

Edith was a sculptor, and the ‘curled-up figures’ of the poem refer to the dark wooden sculptures of tortured bodies that she made, and which lined her dining room in glass cases. That dining room also had a large, patterned rug hanging on the wall – a Slavic fashion that struck me as strange when I was a child. My brother and I, on family visits to Sheffield and London, would make up strange games to entertain ourselves, including making a bee graveyard in the gardens of my grandma’s block of flats. My memories of our visits to my great-aunts, my widowed Yorkshire grandma, and to Edith and Otto are some of my earliest, and rather confused, so the flat of the poem is a combination of several different places. ‘Survivors’ tries to capture some of the atmosphere of that time for us, as small children who had no idea, yet, about our family’s recent past.

|

| Mary Anne’s mother and her sisters |

Mary Anne Clark

To me, each of my aunts has a different set of memories, associations, and attributes, and I have learned different things about life from each of them. But they have at the same time a single unified identity - ‘the aunties’. They are a matriarchal herd, a stampede of women with their mother, my Nan, who died two years ago, at the head.

This picture is of my mum (front, second from right) and her four older sisters. It is by my aunt, Celia Paul (back, reflected in the mirror while painting). They are all wearing identical white smocks, which makes them look almost indistinguishable to a casual glancer, but which emphasises the differences in their faces and postures to someone who looks more closely. To someone who knows them, they are immediately recognisable as their individual selves. I think I could tell them apart just by their feet.

Hilaire

Auntie Hil was my favourite aunt. I was so fond of her that I decided, in grade one, that I wanted to be called by my middle name – her name – and wouldn’t answer to the first name my parents had chosen for me. Auntie Hil was cheery and had a lively sense of humour; the sort of person people would strike up a conversation with on the bus or in the street. She often retold these encounters, laced with her infectious laughter. This openness and lack of reserve was alien to me. In my immediate family, introversion was the default mode. She showed me a different way of interacting with the world.

But her most profound, and early, influence on me was as a writer. She was always writing, mostly novels but also poetry, and she never gave up sending her work out, though she had little success. Her example set me on the writing path. After I left Australia and moved to London in my early twenties we occasionally corresponded, and she would end her letters wishing me ‘all power to your writing elbow’.

Auntie Hil died in January 2005, aged just 64. A few months later my niece Ana was born, my parents’ first and only grandchild. Becoming an aunt has given me a new role in the family, one I relish, and was the inspiration for my poem in the anthology.

|

| Rob and his family |

Rob Hamberger

Rob and his family After my father left when I was six years old, my childhood and adolescence was surrounded by women: my maternal grandmother Jane, my mother and her three sisters – Suzie, Nettie and Hannah – their half-sisters Alice and Harriet and their cousin Anna. They peopled my landscape, tall as standing stones. Playing with my brothers and cousins on the front-room carpet in my Nan’s flat, women’s voices lilted their continual accompaniment to our games, sharing jokes and stories with each other; another comment chucked into the criss-crossing mêlée of words; laughter suddenly blossoming over my head. Laughter I never fully understood, though I wanted to share it because it made me happy.

Aunt Anna had a great sense of style. When she had a new passport photo taken for our trip to old wartime friends in Holland she sounded delighted as she showed it to us: “It makes me look like a French tart!” She worked for the London Underground at Bethnal Green Tube station. I associate her with singing, especially at the crowded Boxing Day parties in our Whitechapel flat. I catch her singing down the years with my mother. They sway together with drinks in their hands, Aunt Anna balancing a fag between her fingers:

Call round any old timeMy poem came from a workshop led by Naomi Foyle, where she asked us to celebrate a relative. The words flowed easily, as if they’d always been on the brink of being written.

Make yourself at home –

* * *

The Emma Press Anthology of Aunts is available to buy now on our website.

No comments:

Post a Comment